Commander Samuel Dealey

Commander Dealey was born on September 13, 1906 in Dallas, Texas, where he attended Oak Cliff High School. He graduated from the Naval Academy in June 1930. Dealey had duty on the battleship USS NEVADA (BB-36) before training as a submarine sailor.

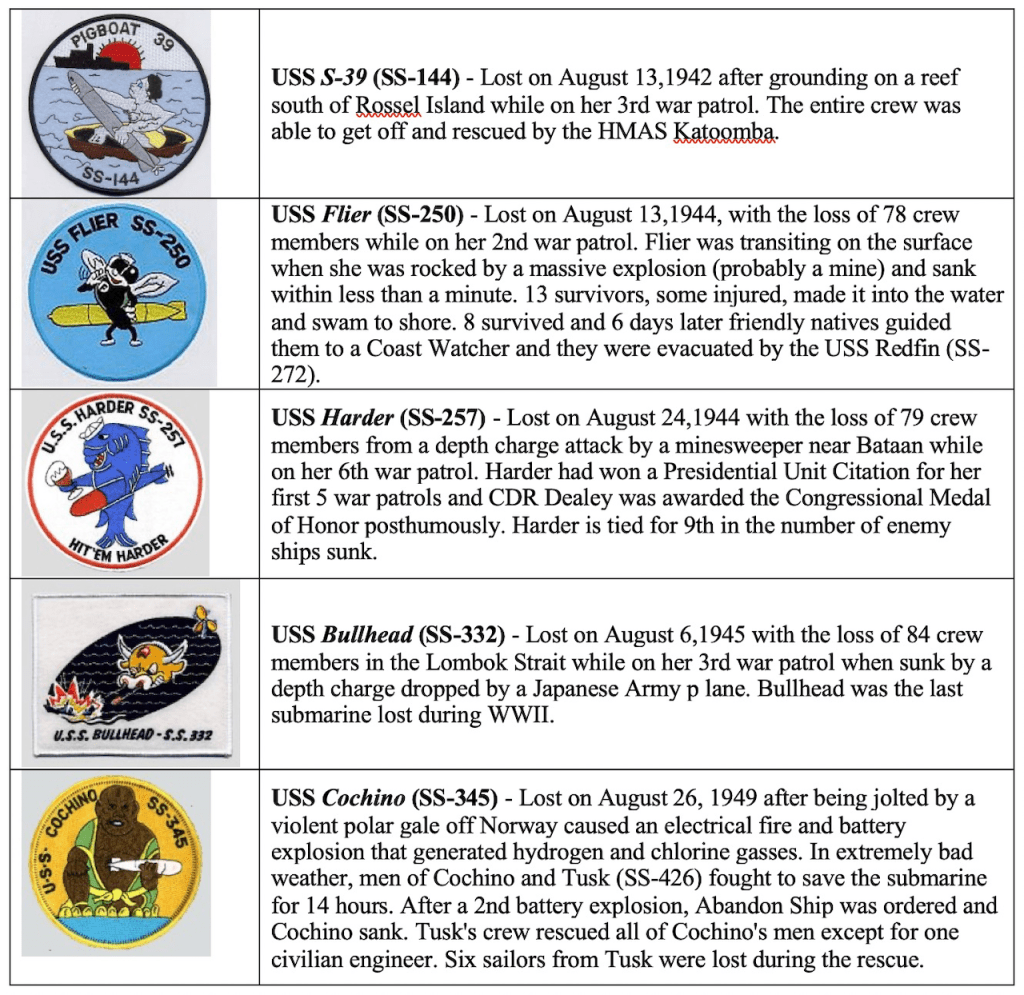

He assumed command of USS HARDER (SS-257) upon her commissioning on December 2, 1942. Commander Dealey guided his submarine deep into enemy waters, wreaking destruction on Japanese shipping.

On HARDER’S fifth war patrol, Commander Dealey pressed home a series of bold and daring attacks, both surfaced and submerged, which sank three enemy destroyers and damaged two others. For his exceptional gallantry in these actions, Commander Dealey received the Medal of Honor.

The CITATION reads:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as Commanding Officer of the USS HARDER during her 5th War Patrol in Japanese-controlled waters. Floodlighted by a bright moon and disclosed to an enemy destroyer escort which bore down with intent to attack, CDR Dealey quickly dove to periscope depth and waited for the pursuer to close range, then opened fire, sending the target and all aboard down in flames with his third torpedo. Plunging deep to avoid fierce depth charges, he again surfaced and, within 9 minutes after sighting another destroyer, had sent the enemy down tail first with a hit directly amid ship. Evading detection, he penetrated the confined waters off Tawi Tawi with the Japanese Fleet base 6 miles away and scored death blows on 2 patrolling destroyers in quick succession. With his ship heeled over by concussion from the first exploding target and the second vessel nose-diving in a blinding detonation, he cleared the area at high speed. Sighted by a large hostile fleet force on the following day, he swung his bow toward the lead destroyer for another “down-the-throat” shot, fired 3 bow tubes and promptly crash-dived to be terrifically rocked seconds later by the exploding ship as the HARDER passed beneath. This remarkable record of 5 vital Japanese destroyers sunk in 5 short-range torpedo attacks attests the valiant fighting spirit of CDR Dealey and his indomitable command.”

He was lost with his submarine during its sixth war patrol, when HARDER was sunk August 24, 1944 by a depth charge attack off Luzon, Philippines.