By Nelson (Maynard) Greer, EN1(SS)

Damn, we had fun. Some of it sure didn’t seem much like fun at the time, but looking back through the mists of time, it was all fun.

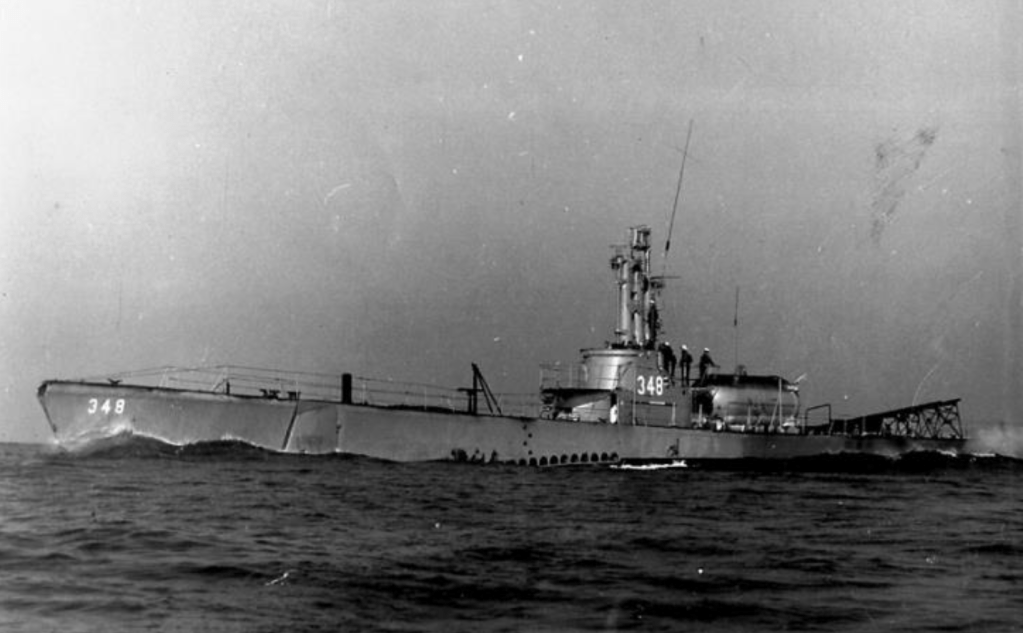

It was summertime, 1965, and the USS Cusk (SS 348) took on a full load of food and fuel, left Pearl Harbor in our wake, and headed for adventure in the Western Pacific. I don’t recollect us doing any Northern Runs that WESTPAC trip. We left the Russians to them new-fangled nukes and the more modern diesel boats. The glory days of the Cusk were the late 40’s, when she was the first submarine in the world to fire a guided missile. Later she got the Guppy II treatment with snorkel, new sail, and updated electronics, but basically, she was a WWII boat, fast on the surface and slow underwater. So, some guy at the top decided to let us patrol the Viet Nam area.

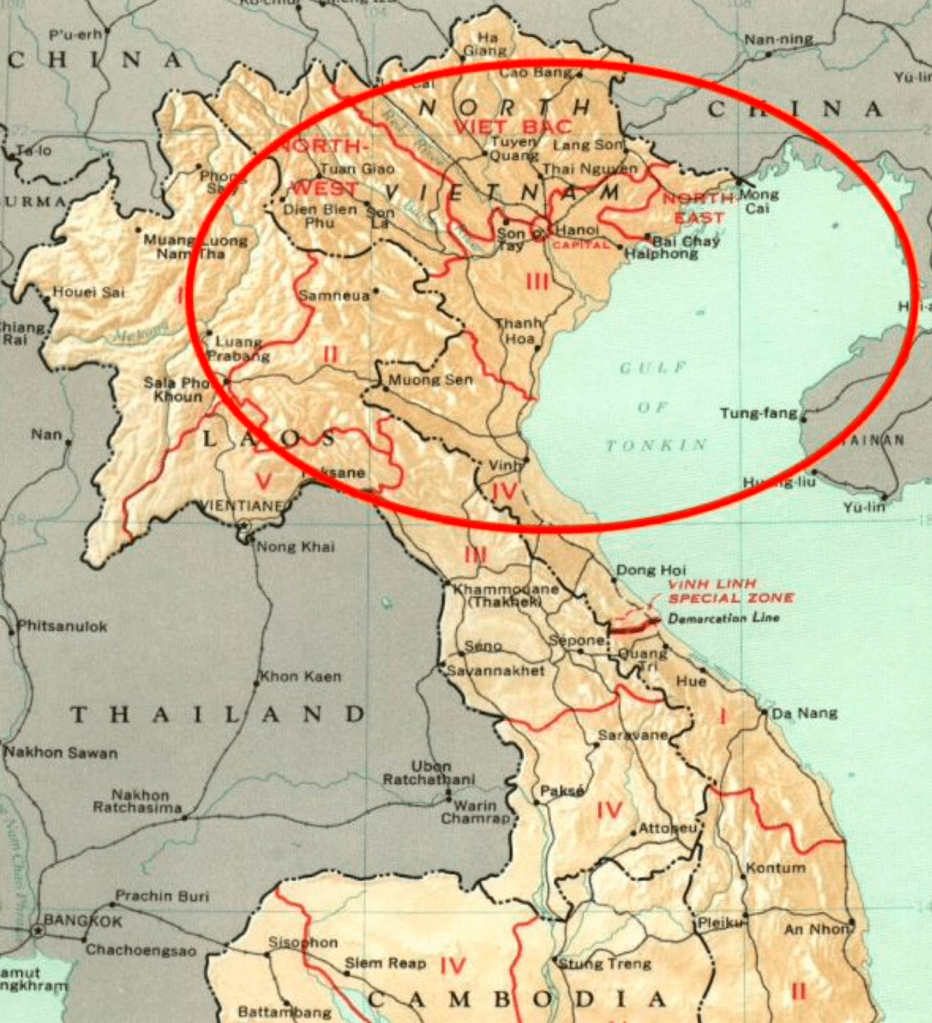

We made 2 or 3 patrols down south, so for brevity I’ll lump everything I remember into one tale. We were assigned lifeguard duty, with a 100 mile grid to patrol. If any airdales decided to ditch in our area on the way back to their carriers, our job was to rescue them. We cruised on one engine at about two knots, submerging once a day just to prove we were still a submarine. Nothing happened to any flyboys in our area, but plenty of irritating stuff happened to us.

You could always tell the Electricians on the boats by their dungarees. They got way too close to battery acid, and their clothes looked like they were headed to a swiss cheese convention. On the Cusk, the whole crew looked like that. Those old boats had a ‘closed cell’ ventilation system, where the Exhaust Blower took a suction directly from our 252 battery cells. This caused battery acid to get into the steel ventilation piping and we know who always wins that battle. The piping runs along the overhead from the Forward Battery compartment, through the Control Room and After Battery compartment, and ends at the Exhaust Blower in the Forward Engine room. The crew worked ate and slept underneath this piping. I remember tasting and then tossing out food when battery acid dripped in my plate. We could never tell if acid dripped in the bug juice, we drank cause the mess cooks mixed it so strong we probably could have used it in the batteries.

The worst acid leak was on the Exhaust Blower itself. And directly underneath was the perfect spot for the throttleman to stand while operating our two distilling units. So, when making water that we weren’t allowed to shower with, we would have acid dripping on us. We had to amuse ourselves at sea somehow so Lonnie Moo Johnson and myself decided to have a “whose dungarees will rot off first” contest. I don’t remember the prize; I suppose it was an ice cold San Miguel beer in Olongapo or something just as useful. After 10 days we compared what was left of our uniforms and Lonnie Moo won. He must have cheated and rolled on the deck to get some extra acid, because I know I stood under that blower 8 hours a day for all 10 days.

Now, the Supply Blower is right next to the Exhaust Blower and there may have been some acid carryover to it. The pipe coming out of the blower splits into a Y shape and forces fresh engine room air through two smaller pipes into the forward part of the boat. Well, right at that Y the piping rotted out and the fellers up forward weren’t getting enough fresh air. We looked at our coffee cans and other types of sheet metal and couldn’t come up with anything to repair it with. Then some genius said, “Dungaree pants”. Somebody had a new pair without any acid holes, we replaced the sheet metal piping with the bell bottom trousers, secured it with that there newly invented duct tape, and they held up until we got into Subic Bay for an upkeep.

Cruising off the coast of Vietnam in the fall was HOT, HOT, HOT! The Cusk had two 12 ton air conditioning units in the After Engine room. Not really good enough to cool the boat very well, but when they both broke down, son-of-a-bitch, it went from just HOT to absolutely miserable. We tried to cool the boat by opening all the watertight doors, closing the main induction, drawing air through the boat from the conning tower hatch to the engines. That helped everybody except the electricians cause the humid Tonkin Gulf air shorted out everything between the conning tower and the engine room. So, we opened the main induction and went back to being miserable again. During the day we were allowed to sit inside the superstructure above the forward torpedo room where we could scoop up cool salt water and pour it over ourselves, which gave us some temporary relief. No one wore shirts except the cooks and mess cooks, as we didn’t want none of their manly chest hairs in our chili con carne. One day I was sitting in the mess decks, and a cook, Ptomaine Greer (no relation), came out of the galley and took off his sweat soaked tee shirt. I have never seen a rash that large before or since. It looked like he was wearing a red tee shirt. I tell you; it was absolutely miserable.

We all know the Government would rather waste a dollar and do nothing than spend a dime to fix a problem. Here is a story to illustrate that truth. The General Motors 278-A diesel engine has four exhaust valves in each of its 16 cylinder heads. The valves have two grooves near the top of the stem. Two ‘keeper’ halves fit around each valve and have two ridges (called ‘lands’) on the inside that fit into the valve grooves, while the outside of the keepers fit into a tapered cup that sits on top of the valve spring. The keepers keep the valve connected to the spring. For you non engineer types, the spring holds the valve shut whilst fuel is exploding inside the cylinder.

The Cusk received a large shipment of refurbished heads prior to deploying to WESTPAC. We overhauled number Two Engine using 16 of the ‘new’ heads just before getting underway. It ran just fine in port. Departure day dawned, and we headed toward the Land of the Rising Sun. A of couple days out and suddenly, BAM, BAM, BAM, BAM shut that engine down, there is something wrong there. Pull the valve covers and, hey, here is the culprit, an exhaust valve is missing, and the only place it could be is between the piston and the head. Diesel engines have a 16 to 1 compression ratio, so there isn’t a whole lot of clearance in there.

So, we yank that head off, and there is our mangled valve laying on top of one very beat up looking piston. The bottom side of the head has matching scars from the wayward valve. We strip the head, salvaging the salvageable parts. “Hey, these valve keepers only have one land” says some sharp sighted sailor. The valve keepers need two lands so are only doing 50% of their job. We check the spare head we are about to slap on. The keepers have just one land. We check all of our recently received spare heads, same thing. No choice, we got to use the crappy keepers. Next day that engine goes BAM, BAM, BAM, BAM again, same story, different cylinder. And so, it goes for the two weeks it takes us to reach Yokosuka, Japan.

We figure we can just get some new keepers from the supply system in Yoko and the problem is on its way to being solved, right? ‘Supply’ had plenty of keepers in stock and they sent them right away. You guessed it, all of them were the new improved one land type guaranteed to drop the exhaust valve into the cylinder while the engine was running. Frantic phone calls were made, but no one cared. Don’t you know there is a war going on down south?

The joke on Jimmy boats was that if there were two coats of paint on the bulkhead outboard of the engines, you would have to chip off one coat for clearance in order to slide a head up off of its studs. Not a lot of working room out there, and hotter ‘n hell if the engine has been running. Changing an outboard head at sea was way low on our list of favorite things to do. The cool waters by the dock in Yokosuka kept the engine room at a comfortable temperature, so we formed a plan to avoid future pain. We moved the five gallon cans of coffee, flour, and sugar we had stored there and pulled all eight heads off the outboard side of that newly overhauled engine. Then we took the eight most easily accessible heads off the inboard side of the other engines, installed the good ones outboard, and replaced them with the faulty heads. Now we knew the cylinders likely to fail were easy to get to.

After a while we were champion head changers. Four hours after hearing that dreaded BAM, BAM, BAM, BAM the engine would be on the line again. If there was a puka in the piston, add two hours. Lacerated liner, add another two hours,

These heads weren’t the dinky things like on your lawn mower. They were over a foot square, and maybe 8 inches thick. They weighed 186 pounds. The circumference of my wrists grew an inch that WESTPAC trip. I could just barely lift one and carry it around. Lonnie Moo was about 5 feet tall and 6 feet wide, and he could lift one in each hand and waddle down the passageway. A point of pride was being able to cradle a head in your arms, and step through the hatch with it into the other engine room. The chief was keeping track, and said we had changed 96 heads by the time we got back to Pearl.

As for liberty, if you were there in those days, you remember what we did in Honcho 1, 2, and 3 in Yokosuka, the Wan chai District of Hong Kong, and on Olongapo’s’ Magsaysay Drive. If you weren’t there, you can only envy us.

Damn, we had fun.

Thanks for a wonderful tale!

LikeLike